Marijuana was first criminalized in the US under the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act, which was replaced by the 1970 Controlled Substances Act (CSA) that remains in force to this day.

The CSA classifies drugs under five ‘schedules’ determined by the presumed addictiveness and potential for abuse of the substance weighed against its medical value. As a Schedule I substance under the CSA, cannabis is considered to have no medical value with high potential for addiction and abuse, alongside drugs such as heroin and cocaine.

Conflicting Federal and State Cannabis Laws

Federal marijuana criminalization was largely uncontested by states for decades until 1996 when California became the first state to pass legislation – spurred by a voter-approved ballot initiative – to legalize medical marijuana. Under cannabis federal law, doctors in California couldn’t ‘prescribe’ it but they were able to ‘recommend’ it under the First Amendment.

This isn’t to say California’s medical cannabis program operated in its early years free of federal interference. Before it got off the ground, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) threatened to take action against doctors suspected of recommending marijuana to patients, while the US House of Representatives resoundingly approved a symbolic resolution against California’s decision to legalize medical cannabis.

Even as other states soon joined California in reforming their marijuana laws to recognize the plant’s therapeutic value and expand access to patients, federal law enforcement was frequently hostile to state-legal medical marijuana activity. Between 1996 and 2012, the federal government spent nearly half a billion dollars interfering in states’ medical cannabis programs. More than 500 raids and dozens of prosecutions were dished out against groups and individuals acting in compliance with state law.

These raids and prosecutions continued in spite of the judicial and executive branches of the federal government softening their approach, at least in rhetoric, toward state-legal medical marijuana programs. In a 2008 campaign pledge, President Barack Obama said he would not seek to interfere in state’s medical cannabis programs, while a 2009 DoJ memo advised “prosecutorial discretion” when it comes to enforcing federal law against state-legal medical cannabis programs.

The conflict between state and federal marijuana laws only started to seriously tilt in favor of states seeking to reform their marijuana laws in 2012, when Colorado and Washington became the first states to legalize for recreational use and did so without significant federal blowback. On the contrary, the following year the DoJ published another set of federal cannabis law guidelines – the Cole memo – concerning states that had legalized adult-use cannabis. Its guidance echoed those of the 2009 memo regarding medical marijuana, yet federal agencies and prosecutors now appeared to take its instructions more seriously. Raids and prosecutions against marijuana operators in compliance with state law tapered off.

The advisory force of the two DoJ memos was strengthened in 2015 when the US House of Representatives passed a federal budget rider – the Rohrabacher–Farr amendment – prohibiting the DoJ from using federal funds to interfere with state medical marijuana laws. While the vote didn’t change the legal status of cannabis and must be renewed every fiscal year, it marked – at the seventh attempt – the first time either chamber of congress voted to protect access to medical marijuana under state law. These protections were upheld in several landmark federal court rulings, such as the 2015 U.S. v Marin Alliance for Medical Marijuana (Northern District of California) where the presiding judge ruled the Rohrabacher–Farr amendment “forbids the Department of Justice from enforcing this injunction against MAMM to the extent that MAMM operates in compliance with state California law.”

Not long after, the DoJ dropped its case against Harborside Health Center, a medical cannabis dispensary in Oakland. A few months later, state-legal medical marijuana operators scored their biggest victory yet in the August 2016 case of US vs McIntosh in the federal 9th Circuit Court. Not only did the judge order the DoJ to abide by the Rohrabacher–Farr amendment, he also ruled that in future federal prosecutors must prove at a preliminary hearing that the defendant violated state medical marijuana laws.

This tacit acceptance of state-level marijuana legalization, now by all three branches of the federal government, has taken the US past the point of no return. The heavy-handed days of enforced prohibition appear over in states that decided to diverge from federal marijuana laws. A rupture has now been established between the nascent state-legal cannabis industry and federal marijuana law that’s yet to be resolved.

Why Federal Marijuana Law Reform Is Both Necessary and Inevitable

While the federal government accepted that enforcement of federal marijuana laws is not desirable in states that passed marijuana legalization legislation, this truce is not a long-term solution. There are serious shortcomings to the current protections that will need to be addressed sooner or later.

This much was made clear when President Donald Trump’s first pick for attorney general, Jeff Sessions, decided to rescind the Cole memo in 2018, while Trump himself considered removing the Rohrabacher–Farr amendment from the 2021 federal budget. In practice, however, these episodes served only to prove the difficulty the federal government faces in rolling back newly-established protections for states that legalized cannabis. Trump quickly backed down while Jeff Sessions’ call for a “return to the rule of law” barely registered a change in states where marijuana was now legal. This is because the federal government is more or less entirely dependent on state police forces to enforce federal cannabis laws, and those police forces primarily act under the authority of state attorney generals who – at least in states that legalized marijuana – do not share Sessions’ zeal for enforcing federal marijuana laws.

So while the federal government cannot easily force a return to marijuana prohibition across the US, the de facto suspension of federal marijuana laws in states that opted to legalize is also not a tenable long-term proposition.

The Cole memo doesn’t automatically confer legal protections or rights on state-legal cannabis businesses or consumers if a prosecutor chooses to ignore the advice and pursue a marijuana-related conviction, however unlikely that conviction may prove to be. The memo also does nothing to ensure state-legal cannabis businesses can access banking and legal services, as those providers may fear federal reprisals. Marijuana businesses also can’t be sure of intellectual property rights, insurance protections or even the enforceability of standard business contracts without the support of federal law. Cannabis consumers in legal states also face repercussions with regards to, for instance, employment, naturalization, probation, parole and family law settlements.

There’s also the broader issue of inequity under US law. How can a person in one part of the country be serving a life sentence for an offense that another person engaged in the same practice in another part of the country is earning millions from? This discrepancy has led federal judges to refrain from following federal sentencing guidelines for cannabis offenses, with one judge who issued a reduced sentence doing so on the basis that the offense “bears some similarity to those marijuana distribution operations in Colorado and Washington that will not be subject to federal prosecution.”

If going back to federal marijuana prohibition across the US is impossible, and the de facto suspension of federal cannabis laws in states that legalized marijuana is untenable in the long-run, then the only option left is for legislative action on marijuana reform at the federal level.

Federal-level Marijuana Reform Efforts

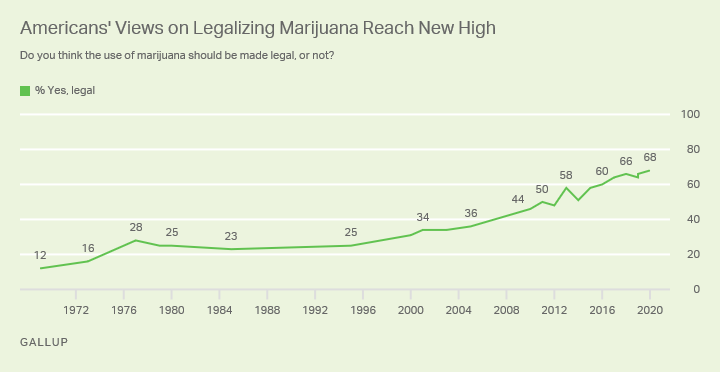

In the years since these minimal protections for state-legal cannabis programs were established, marijuana legalization’s momentum has gone into overdrive. As of February 2021, 15 states have legalized adult-use cannabis, while 46 states have passed laws allowing some form of medical marijuana. This momentum is reflected both in nationwide polling on the issue which consistently finds majority support for federal marijuana legalization and its near-unanimous adoption by Democrats as a policy position, in spite of President Joe Biden and the Democratic National Committee’s hesitancy to embrace the measure.

This hasn’t gone unnoticed by federal lawmakers. Recent years have seen a flurry of cannabis reform bills submitted to both chambers of congress, such as the Marijuana Freedom and Opportunity Act to deschedule cannabis from the CSA and the STATES Act to ensure state-level marijuana legalization is recognized in federal law. In 2018, President Donald Trump signed the Farm Bill into law which legalized hemp containing less than 0.3 percent THC across the US. In 2020, the House of Representatives included provisions of the SAFE Banking Act – passed as a standalone bill in 2019 – in its initial coronavirus relief package to ensure access to financial services for state-legal marijuana businesses, but these were removed from the final version following a standoff with Senate Republicans.

Most tellingly, at the end of 2020 the US House of Representatives moved to federally decriminalize cannabis when it passed the Marijuana Opportunity, Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act – the first time a chamber of congress voted to end federal marijuana prohibition. In previous years, when the Republicans controlled the Senate, it’s more than likely the MORE Act would now be lying around the upper chamber gathering dust. Now, with the Democrats in control of both chambers, there’s every chance of federal-level marijuana reform in 2021.