The Colorado Supreme Court ruled that probable cause is required before subjecting individuals to sniff tests from dogs trained to alert police to the presence of marijuana.

Before, the dog sniff tests were the basis for establishing probable cause for a search, but now law enforcement must have sufficient evidence to authorize a search prior to using a marijuana-trained dog.

According to Sam Kamin, a law professor at the University of Denver who studies marijuana law and policy, the ruling “renders the dogs trained to detect pot useless in most situations.”

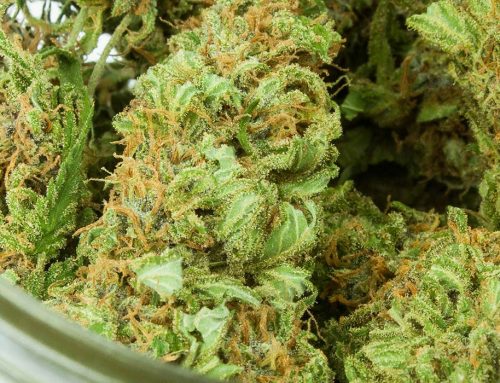

Police dogs, often referred to as K-9s, have been trained to detect marijuana for decades. The practice has recently come under greater scrutiny though since Coloradans voted in 2012 to legalize recreational possession of a limited quantity of cannabis, because the dogs may draw attention to a perfectly legal amount of marijuana.

In the majority’s decision, Supreme Court Justice William Hood wrote that, “[T]he dog’s sniff arguably intrudes on a person’s reasonable expectation of privacy in lawful activity. If so, that intrusion must be justified by some degree of particularized suspicion of criminal activity.”

The narrow 4-3 ruling widens the divide between state and federal law enforcement’s investigative powers in relation to marijuana.

Colorado officers using K-9s must now adhere to the same standards required for other searches of property. This means they must have a warrant before the sniff test, or that the situation fits narrow criteria outlined by state law which permits searches without a warrant.

Irrespective of the ruling, Colorado law enforcement agencies had already begun phasing out marijuana-trained dogs with K-9s who do not alert handlers to the drug. Out of the 120 police dogs in Colorado, less than 20 percent are still trained to detect cannabis.

In spite of the three dissenting votes against the ruling, the decision is similar to how other state courts have considered dogs’ sniff tests for drugs, according to David Ferland, executive director of the United States Police Canine Association.

“What Colorado is doing does not surprise me,” Ferland said. “That’s not going to be earth-shattering.”

The decision does not affect the activities of federal law enforcement agencies, like the Drug Enforcement Administration, operating in Colorado.

Still, the ruling brings attention to the complications resulting from the divergence between state and federal marijuana laws.

According to Chief Justice Nathan Coats, the ruling establishes a system whereby a sniff test is considered a search under the state constitution, but not the federal constitution. In his dissent, he described the majority’s opinion as “deeply flawed.”

Hood, in the majority opinion, instead emphasizes the need to consider Colorado’s specific laws.

“To the extent we end up alone on a jurisprudential island, it is an island on which Colorado voters have deposited us,” he wrote. “Our role is not to question their decision. Rather, it is to apply the logic of existing law to a changing world. Though we are the first court to opine on whether the sniff of a dog trained to detect marijuana in addition to other substances is a search under a state constitution in a state that has legalized marijuana, we probably won’t be the last.”