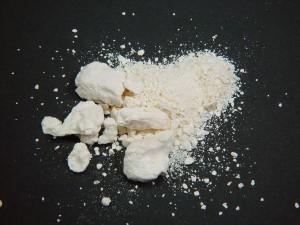

Powdered cocaine and crack are essentially the same drug. They come from the same plant, they contain the same chemical, and they work on the brain in similar ways.

Even so, the government has long taken a much more punitive approach to people who use crack than it does to people who use cocaine hydrochloride, the powdered form of the drug. At least one presidential candidate has promised to end that disparity, a lingering holdover of 1990s anti-drug laws.

Even so, the government has long taken a much more punitive approach to people who use crack than it does to people who use cocaine hydrochloride, the powdered form of the drug. At least one presidential candidate has promised to end that disparity, a lingering holdover of 1990s anti-drug laws.

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said at a rally in October that she would stop imposing harsher prison sentences on crack users than on powdered cocaine users. The announcement came as Clinton unrolls an ambitious plan to reform the troubled criminal justice system.

Clinton is still widely considered the front-runner for the Democratic nomination next year, though former Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders has made it a competitive race. Both candidates have promised to change harsh sentences for marijuana, cocaine, and other drugs.

“Extensive agenda” to be outlined throughout fall

Clinton planned to outline her “extensive agenda” for criminal justice reform throughout the fall. Her proposals include changes to sentencing laws and a bill banning racial profiling by police. She announced her plan to reform cocaine sentences during a speech Oct. 30 in Atlanta, where she launched an “African Americans for Hillary” campaign.

Clinton used the event to unveil her criminal justice proposals, including changes to policing, incarceration, rehabilitation, and re-assimilation of released inmates into society. She had scheduled another speech on the subject in South Carolina in November, to be hosted by the local NAACP.

Her reform campaign is designed to end what she calls the “era of mass incarceration” in America, an era that has disproportionately affected African Americans. Part of the plan will include the push to end cocaine sentencing disparities, which also hit blacks harder than any other group. And she has called for legislation to prevent law enforcement from using race or ethnicity as grounds to launch routine investigations.

Ending the era of mass incarceration

The disparity between crack sentences and sentences for powdered cocaine has existed since the Reagan era, when the United States experienced a supposed “epidemic” of crack addiction (an epidemic that was exaggerated by the media). Congress passed a law in 2010 that cut the disparity from a ratio of 100:1 to a ratio of 18:1, and Clinton said she plans to go further.

Still, the disparity continues to ruin lives across the country, usually the lives of low-level, non-violent offenders who neither make nor sell drugs.

Crack and powdered cocaine are both extracted from the leaves of the coca plant, which grows almost exclusively in South and Central America. Crack is a hard, rock-like cocaine paste also known as “base” or “freebase.” Smoked, it produces an incredibly intense euphoria sometimes described as a full-body orgasm.

Powdered cocaine is a processed form of crack

During its heyday in the late 1980s and early 1990s, crack was especially popular in low-income neighborhoods and communities, in part because it is cheaper and in part because it is more potent. According to government data, almost 80 percent of Americans convicted of crack-related crimes in 2009 were black.

“Crack and powder cocaine are two forms of the same drug, and continuing to treat them differently disproportionately hurts black Americans,” Clinton’s campaign said in a background memo.