Back in 2016, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) announced that it would now accept applications to grow federally-approved marijuana for medical research purposes. Three years and 25 applications later, researchers are still awaiting a response.

Frustrated with the lack of progress, a group of researchers recently filed a lawsuit against the DEA in the hope that a federal court may finally force the agency to act.

While the federal government has provided marijuana to scientists since 1968, the only government-sanctioned cannabis available to researchers is produced by the University of Mississippi on one sole farm.

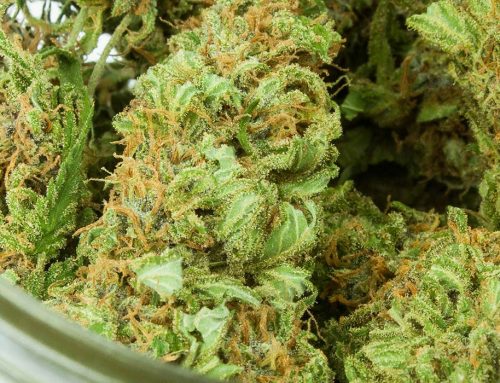

Not only is the quality of the product notoriously bad – one study suggests the cannabis grown there is genetically closer to hemp – but the explosion of interest in medical cannabis research in recent years means that there is simply not enough to go around. So scientists have been pleading with the federal government to allow the cultivation of greater quantities of quality cannabis that can be used for research purposes.

The DEA finally relented in 2016, but then former US Attorney General Jeff Sessions took office under President Trump’s administration and stymied the application process as part of his attempt at reinvigorating the federal government’s War on Drugs.

When Sessions left his post, the DEA stated that submitted applications were still under review. But since then, the applications, as well as several letters from members of Congress inquiring as to the status of these applications, have been ignored.

The Scottsdale Research Institute (SRI) is one such applicant, who is now seeking a legal remedy against the DEA in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

The lawsuit, filed on June 11, asks a federal judge to compel the DEA or attorney general to respond to the application within three months.

“While most states in the U.S. recognize that cannabis has medical value, the DEA says otherwise, pointing to the absence of clinical research,” Sue Sisley, principal researcher at SRI, said in a press release. “But at the same time, government regulations and bureaucracy prevent researchers like SRI from ever doing the clinical research the DEA has overtly demanded.”

In a summary of its argument, the SRI wrote that the “DEA’s delay in noticing or responding to SRI’s application is unlawful, unreasonable, and egregious. It contravenes the letter and spirit of the [Controlled Substances Act], seriously harms SRI, and hampers SRI’s efforts to help suffering veterans through clinical research.”

Attorney General Bill Barr has indicated that he is more supportive of facilitating medical cannabis research than his predecessor Jeff Sessions, but has thus far not put his rhetoric into practice.

“Everyone—including the agency—agrees that this research is important and that the need for research generally is urgent,” the SRI continue in their summary. “Here, DEA can act with little expenditure of resources.”