Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine found that legal medical marijuana does not lead to lower rates of fatal opioid overdoses.

The new study contradicts the findings of a 2014 study which concluded that states that had legalized medical marijuana saw the rates of fatal opioid overdoses decrease. Many cannabis advocates, doctors and lawmakers used these results as a rationale for legalization.

But the recent study, which follows widespread legalization of medical marijuana, found that new data does not provide any evidence of a link between legal medical cannabis and opioid deaths.

“If you think opening a bunch of dispensaries is going to reduce opioid deaths, you’ll be disappointed,” Keith Humphreys, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and the senior author of the study, said. “We don’t think cannabis is killing people, but we don’t think it’s saving people.”

A paper reporting these findings was published online in June in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

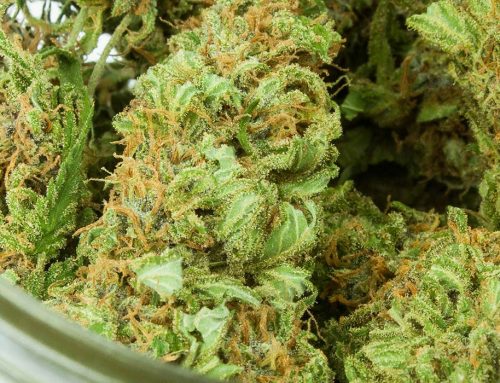

The first state where medical marijuana became legal was California in 1996. By now, 47 states have allowed some forms of cannabis to be used for medical purposes.

The Stanford researchers applied the same method to analyze the issue as the 2014 study. While they found the results of the earlier study were correct, a subsequent analysis of opioid deaths up to 2017 showed that higher rates of fatal overdoses occurred in states that had legalized medical pot.

To proponents of legalization, as well as some lawmakers, the findings of the 2014 study meant that access to legal marijuana would make people use it as a pain relief or recreational substitute for opioids. But even when comparing states with different levels of restrictions placed on cannabis, the researchers found no evidence to show that the extent of restrictions affects opioid overdose mortality.

“Accounting for different types of laws didn’t change the bottom line,” postdoctoral scholar and lead author of the study, Chelsea Shover, PhD, said.

Additionally, the researchers said it is unlikely that the rate of medical marijuana use – at 2.5 percent – among the U.S. population is too low to affect opioid deaths statistics.

According to Humphreys, the findings of the 2014 study likely reflected the states’ economic and political conditions that led to earlier legalization in the first place. Those states were wealthier and more liberal, and provided access to addiction treatment and naloxone, which is used as an antidote for opioid overdoses.

They also have lower rates of incarceration for drug use, Humphreys said. By the time people are released from prison, their tolerance for drugs decreases, which can lead to overdoses if they go back to using similar amounts of drugs as before incarceration.

Lower rates of opioid deaths in the states that legalized early weren’t due to medical marijuana legalization, but “it was something else about those states,” Humphreys said.

Both researchers admitted that medical cannabis legalization could be beneficial, and that studies of its impacts should continue.

Shover said that “there are valid reasons to pursue medical cannabis policies, but this doesn’t seem to be one of them.”

“I urge researchers and policymakers to focus on other ways to reduce mortality due to opioid overdoses,” she added.