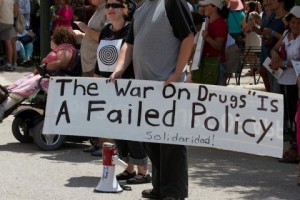

Few words bring disgust to the heart of any true marijuana advocate like “the War on Drugs.” It’s a hard-edged term of the Nixon era, one designed to evoke a winnable battle against vague but evil forces, and its use is now widely viewed as an unmitigated catastrophe.

In part that’s because this futile “war” was launched mostly against a vast sea of helpless addicts. Seen as the enemy in its most human form, they were easy to shame, punish, and blame for the problems of an imperfect society. It was only in recent years, after addiction began to hit white, conservative America, that this view began to change.

In part that’s because this futile “war” was launched mostly against a vast sea of helpless addicts. Seen as the enemy in its most human form, they were easy to shame, punish, and blame for the problems of an imperfect society. It was only in recent years, after addiction began to hit white, conservative America, that this view began to change.

Now most people outside of law enforcement and the right wing of the Republican Party acknowledge the drug war has been a colossal failure. But there’s one thing few people seem to agree on: when it began.

1970: Controlled Substance Act

The modern notion of drugs as a military foe came about in the early 1970s, during the presidency of Richard Nixon. In 1970, he pushed a series of drug laws through Congress, including the Controlled Substances Act. That law divides legally controlled substances into five categories, each ranked by danger, propensity for addiction, and medical usefulness.

Marijuana was placed in the top category, along with heroin, LSD, and peyote. Reformers have been trying to get it placed in a lower category for many years, with no success, though several lawmakers have pushed the idea in recent months.

1971: Nixon popularized “war on drugs”

It was in 1971 that Nixon first popularized the notion of a “war on drugs.” But in a technical sense, the “war” really began long before that.

In some ways, it can be traced back to an epidemic of addiction that swept the United States in the late 19th century – the patent medicine era. These legal “medicines” typically contained strong doses of heroin, morphine, cannabis, and other powerful drugs. All were unregulated at the time.

Cocaine and heroin addictions raged across the country for decades. By the early 20th century, the epidemic was fading, but not before it gave birth to the idea of prohibition.

1914: Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914

Around the same time, however, states began to enact their own laws barring cannabis possession. Unlike the Harrison Act, these laws didn’t attempt to tax and regulate drugs but rather to ban them outright – an approach that many believed would be unconstitutional at the federal level.

1920: 18th Amendment and Prohibition

That perspective changed in 1920 with the 18th Amendment and Prohibition. For the first time, the federal government passed laws that completely barred its citizens from putting intoxicating chemicals into their bodies, though the law applied only to alcohol.

1933: Prohibition was repealed

Prohibition died in 1933, but the idea lived on. So did much of the police apparatus used to enforce it. Out of that tradition came the Federal Narcotics Bureau, the predecessor to the DEA.

Harry Anslinger ran the Narcotics Bureau from 1930 to 1962, almost as long as J. Edgar Hoover ran the FBI. Anslinger, more than anyone else, may be the starting point of the “war on drugs.”

1937: Marihuana Transfer Tax Act

Entirely on his initiative, Congress banned all marijuana in 1937 with the Marihuana Transfer Tax Act. Like the Harrison Act, this new law sought to “regulate” marijuana, but in such a way that no one could grow, sell, possess, or use cannabis for any reason. It was a tax law, but it criminalized the drug. And for practical purposes, it marks the true start of the drug war.

The term wasn’t common at that time, although it occasionally appeared in newspaper headlines. But Anslinger and his many deputies openly treated their jobs as a war, one they were convinced they could win. Nixon may have made the words popular, but he certainly didn’t invent the bad policy behind them.