President Richard Nixon declared war on drugs in June 1971. At the time, the United States was fighting a literal war in Vietnam that was unpopular with young people, in part because young men were being drafted to serve in that war. For many, racism was another reason to oppose the war in Vietnam.

In 1967, for example, Martin Luther King, Jr., spoke out against American involvement in the war, saying:

And so we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. And so we watch them in brutal solidarity burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago. I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor.

At roughly the same time, the world-famous African American boxer Muhammad Ali, said this regarding his opposition to being drafted to fight in Vietnam:

My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father. … Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people?

The words of King and Ali did not go unnoticed in Washington, D.C. John Ehrlichman, who served Nixon as an attorney and assistant to the president for domestic affairs, put it this way:

The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people….We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.

After Nixon, another Republican president, Ronald Reagan, again championed the war on drugs. First Lady Nancy Reagan gave a speech in 1986 often remembered for its catch phrase, “just say no.” What is less often remembered is that the Reagan administration began antidrug policies that disproportionately affected people of color, for example by instituting mandatory minimum prison sentences for crack cocaine. More than 80 percent of those arrested were black, even though blacks and whites use drugs at roughly the same rates.

A video by Jay Z offers more details on Reagan’s continuation of the war on drugs.

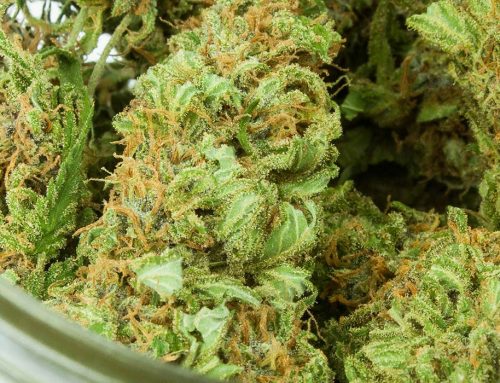

Marijuana

The racism behind the war on marijuana goes back farther than 1971, however. The rationale for making marijuana illegal nationally, with passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 (four years after the United States abandoned its failed prohibition of alcohol), was racist.

Hemp was a popular crop in the United States until a large number of Mexicans, fleeing the country’s revolution of 1910-1920 and Cristero War of 1926-1929, emigrated to the United States. At the time, the United States was more concerned with excluding Asian immigrants; Mexican immigration was generally legal. About 20,000 to 100,000 Mexicans per year emigrated during the years of violence at home. One thing they brought with them was their language, and so hemp began to be called by its Spanish name, marijuana. (Knowledge of how to grow psychoactive buds from the female hemp plant is centuries old.)

Prejudice against the Spanish-speaking newcomers led to the prohibition of hemp. As antidrug crusader Harry J. Anslinger put it in 1937: “[Marijuana] is dangerous to the mind and body, and particularly dangerous to the criminal type, because it releases all of the inhibitions.” The movie Reefer Madness (1936) was part of a propaganda campaign to convince Americans that marijuana dangerously lowered inhibitions—especially among blacks, Latinos, and poor whites, also known as the “criminal type”—making users inclined to rape and murder. This campaign was successful, leading to the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act and the installation of Anslinger as the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

The U.S. government’s war on drugs has yet to be declared over, and racial disparity in enforcement of the nation’s drug laws continues.

What do you think? When will the United States government end its war on drugs, as it did with alcohol? Leave a comment below.